The Inventor of the Chatbot Tried to Warn Us About A.I.

Technological history may not repeat, but it occasionally rhymes. Last September, ChatGPT, the popular generative A.I. program made by OpenAI, released a voice mode that allowed users to talk to the software. ChatGPT then “talks” back. A few days later, OpenAI’s head of safety posted on X about a surprisingly moving interaction she had with the program:

Just had a quite emotional, personal conversation w/ ChatGPT in voice mode, talking about stress, work-life balance. Interestingly I felt heard & warm. Never tried therapy before but this is probably it? Try it especially if you usually just use it as a productivity tool.

The short post was a rich text, ripe for satirical interpretation—the highly paid, emotionally obtuse Silicon Valley engineer who isn’t familiar with therapy but thinks she’s encountered a worthy simulation of it in the notoriously bug-ridden product her employer produces. Where to begin?

Some observers pointed to the example of ELIZA, a famous early chatbot released in 1966 by MIT computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum. Weizenbaum named his chat program after Pygmalion’s Eliza Doolittle, a working-class woman who passes herself off as an aristocrat after some elocution lessons. Designed to resemble a therapist, the software used a canny set of rules and a therapist’s dialogue script to simulate conversation. The program borrowed a technique from Rogerian psychotherapy by often restating a user’s remark as a question. For example, a user would write that they were unhappy and ELIZA asked why they were unhappy. “This was an elegant way to create the effect of a computer holding its own in a conversation with the user,” observed the writer and game designer Matthew Seiji Burns.

Weizenbaum thought he had created a gimmick, something that might “dazzle” a user but not fool them. ELIZA wasn’t creating understanding between two parties. It was creating “the illusion of understanding,” as he described it. But Weizenbaum didn’t anticipate how much some people wanted to be fooled. Some of Weizenbaum’s colleagues saw opportunity, predicting a coming age of automated chatbot therapy providing low-cost mental health care to all (the celebrity astronomer Carl Sagan was a believer). Users went along with the illusion, wish-casting some greater sense of connection. That willingness to attribute human characteristics to a pile of code even spawned a term: the ELIZA effect.

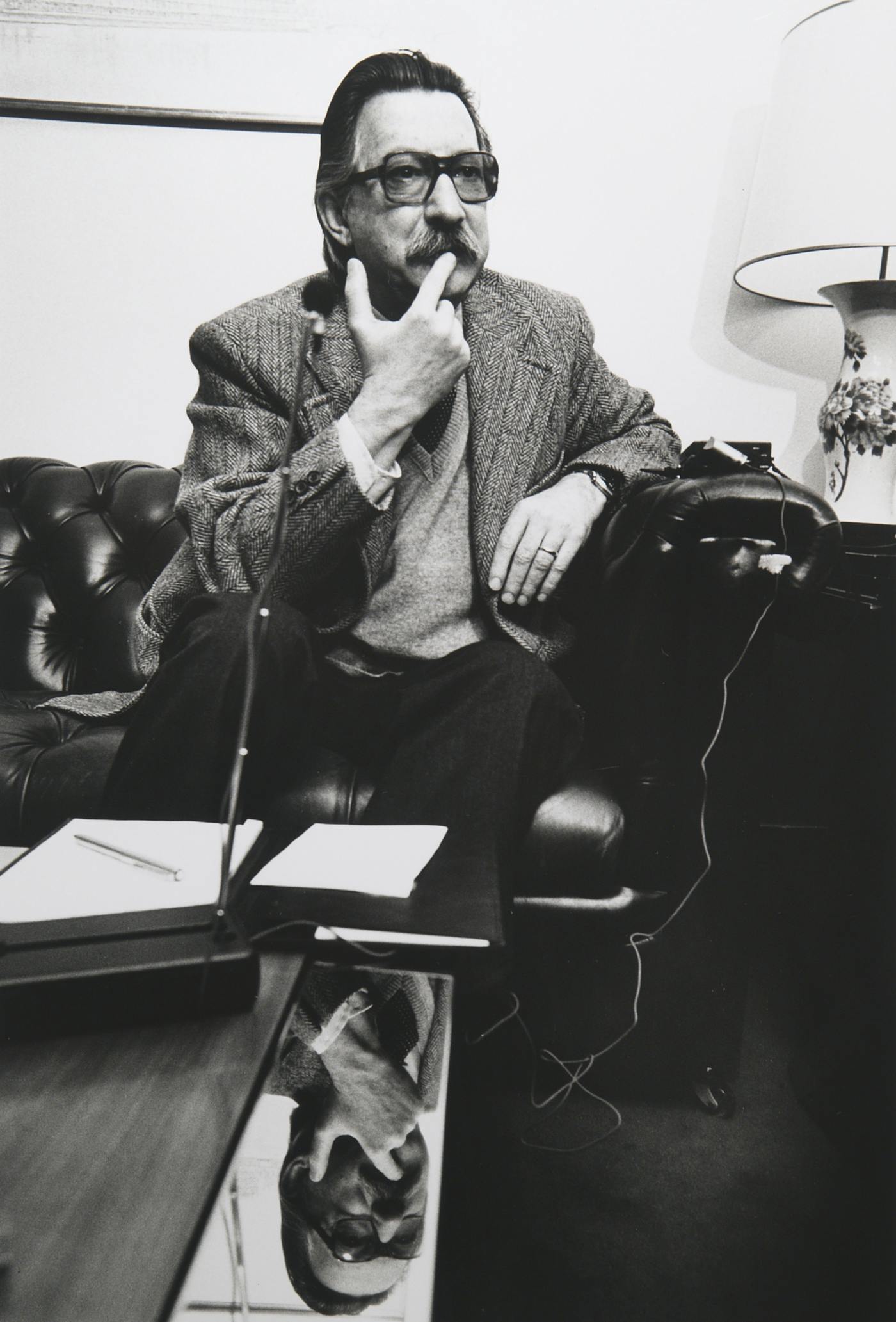

The credulous reaction to his creation transformed Weizenbaum into an important early skeptic of A.I. “Since we do not now have any ways of making computers wise, we ought not now to give computers tasks that demand wisdom,” Weizenbaum wrote in Computer Power and Human Reason (1976), his only published book. As he saw power being given over to computer systems (and those who ran them), he charged his university colleagues with being part of an “artificial intelligentsia” in hock to military research dollars, frog-marching civil society toward a dark techno-authoritarian future wrapped in incomprehensible utopian promises. Almost 50 years later, OpenAI has helped spawn generative A.I. mania and Weizenbaum’s dissident thought has emerged as newly relevant and painfully overlooked. A cranky prophet in the biblical mold, Weizenbaum warned against delusions of digital liberation right up to his death in 2008, at age 85. For scholars and tech critics, Weizenbaum’s ruthless pursuit of first-order questions remains a guiding moral light.

One day in 1966, in an incident that has since passed into computer science legend, Weizenbaum’s secretary sat down to use ELIZA. The secretary soon asked Weizenbaum to leave the room so that she could have privacy. The thought of needing to be alone to talk to a piece of software—much less one that she had seen her boss create—was astonishing, and Weizenbaum would retell the anecdote both in his book and to interviewers for the rest of his life. It reflected something novel and, Weizenbaum thought, disturbing about the relationships people might develop with machines, particularly computers. In attributing to them feelings, thoughts, and identities, people would form harmful attachments to computers, prioritizing their decision-making above human intuition and human needs. In the process, they would surrender to the larger political systems and capitalistic forces that directed technological innovation.

A refugee from Nazi Germany who found himself, as an MIT professor, uncomfortably situated at the center of the military-university-industrial establishment during the height of the Vietnam War, Weizenbaum knew of what he preached. Born in Germany in 1923, Weizenbaum fled with his parents in 1936, settling in Detroit. He studied at Wayne State University, where he helped assemble a computer in an era when such machines took up entire floors of university buildings. After college, he worked on early banking software for General Electric. In the 1960s, MIT called. Growing up first in Nazi Germany and then Detroit, Weizenbaum had developed a sense of racial politics and structural discrimination. Working for large corporations and then a Pentagon-funded university department during the Civil Rights Movement and the Vietnam War, he developed a sense that his own work was out of step with his professed beliefs. While he and his colleagues imagined profound technological possibilities, in practice, many of them did incrementalist research that greased the American war machine. The world had changed, but not for the better.

Nominally a computer scientist with tenure, Weizenbaum has been more accurately described as a social critic who believed that what mattered was less what computers could do—or might one day be capable of doing—than what we make them do. “If the triumph of a revolution is to be measured in terms of the profundity of the social revisions it entrained, then there has been no computer revolution,” Weizenbaum argues in Computer Power and Human Reason. Rather than dismantling the old order, computers arrived in time “to entrench and stabilize social and political structures that otherwise might have been either radically renovated or allowed to totter under the demands that were sure to be made on them. The computer, then, was used to conserve America’s social and political institutions.”

More than an academic, Weizenbaum was a hectoring moral voice, comfortable on the dais denouncing his colleagues for conceiving of the world in increasingly mechanistic, computational terms. Some of them described the brain as a kind of computer—a “meat machine,” in the memorable formulation of Marvin Minsky, who also taught at MIT. Weizenbaum couldn’t stand such analogies, which he found lazy and limiting. “Computers and men are not species of the same genus,” he writes.

The book is a strange amalgam of Heideggerian ruminations on the nature of tools, coding problems, and puzzles; a programmer’s thoughts on language and psychology; and fierce intellectual indictments of certain emerging tech archetypes, like the “compulsive programmers’’ who wanted to reorder society according to machine logic. The book is dotted with equations and scraps of code, almost as if he were working out some thoughts on note paper, and Weizenbaum himself modestly suggests that some of the more technical chapters may be skimmable.

But modesty shouldn’t be mistaken for lack of conviction or intellectual verve. In sweeping, richly sourced essayistic chapters, the book probes fundamental concerns about computers, modern industrial capitalism, and the epistemic arrogance of computer scientists who were then being elevated to a new priestly caste. The book’s intellectual excitement derives from Weizenbaum’s refusal to conform and his willingness to insist, while his colleagues were devoting themselves to Pentagon-funded research, that the price of power “is servitude and impotence.” Having plumbed his own unconscious (“a seething, stormy sea within us”) through years of psychoanalysis, in Computer Power and Human Reason Weizenbaum asks us to perform an equivalent self-examination and to do it with “courage.”

For Weizenbaum, there is one central question: “whether or not human thought is entirely computable.” His answer is an unambiguous no, expressed with an aphoristic flair. “Man faces problems no machine could possibly be made to face,” he writes. “Man is not a machine.” Well read and with no special regard for his own academic discipline, he spoke in quasi-spiritual terms about the complexity of the human mind and how it resists reductive logical understanding. As he said at a 1977 conference: “While science can brilliantly illuminate certain aspects of the world, it leaves other aspects totally dark. For these aspects we have to appeal to the artist, the novelist, the musician—to the artist in us.”

Despite his occasional acts of rhetorical bravado, Weizenbaum approached the world with intellectual humility. “I am professionally trained only in computer science, which is to say (in all seriousness) that I am extremely poorly educated,” he writes. His modesty came bearing a wide-ranging curiosity, showing, in Computer Power and Human Reason, an equal comfort with French literature and recondite math and logic puzzles. The latter were a game. The former was the stuff of life. Both had their place.

Entering the technology industry during the early Cold War years, Weizenbaum feared that humans risked becoming too machinelike, suborning their own ideas to computerized rationality. “I had an introduction to the world in my formative years of the miscarriage of the ultimate form of rationality,” he once said, referring to his childhood in Nazi Germany. Weizenbaum followed a politics of refusal, believing that ethics, at their core, were about “renunciation.” What are you for? What can you tolerate? And what are you against? Scientists, he writes, must “learn to say ‘No!’” As Zachary Loeb wrote in his introduction to Islands in the Cyberstream, a book-length interview with Weizenbaum published after his death, “Weizenbaum sought to reawaken the ethical imagination of his peers.”

Arguably, he failed, but he was proud in revolt. “I have pronounced heresy and I am a heretic,” he said in 1977 to The New York Times, which chronicled Weizenbaum’s testy and occasionally hilarious intellectual spats with his colleagues, who once accused him of being a “carbon-based chauvinist”—“a kind of racist” against artificial beings that didn’t yet exist.

However much he may have delighted in debate-stage pugilism, Weizenbaum seemed lonely in his apostasy. He had experienced the trauma of exile and was raised by a domineering father who delighted in telling his son that he was a failure. Haunted by feelings of self-doubt, Weizenbaum dealt with anorexia, depression, and a suicide attempt. Twice divorced, he retired from MIT in 1988 and moved in 1996 back to his native Germany, where he was welcomed. Two documentaries were made about him. The Weizenbaum Institute was established; it publishes a scholarly journal named for him. He became a source of intellectual inspiration for artists, neo-Luddites, and politically attuned filmmakers like Adam Curtis.

In his autumn years, Weizenbaum lectured and gave interviews in German about his deeply pessimistic assessments of technology and climate change. He began speaking in explicitly Marxist terms about the necessity of “resistance against the greed of global capitalism.” Interviewed by a New York Times reporter in 1999, he offered an avuncular diagnosis of the internet’s malaise that has only become more true with time, especially as content and bots made by generative A.I. now flood the internet. “The Internet is like one of those garbage dumps outside of Bombay,” Weizenbaum said. “There are people, most unfortunately, crawling all over it, and maybe they find a bit of aluminum, or perhaps something they can sell. But mainly it’s garbage.”

He remained a public figure until he died of stomach cancer in March 2008. Two months before he died, he participated in a panel at Davos, precisely the kind of bloviating, corrupt, mindlessly techno-utopian milieu that Weizenbaum resented. All the same, the elderly academic sat glumly as the founders of Second Life and LinkedIn extolled a new era of digital connection. Ever the humanist, Weizenbaum said that none of it mattered as long as American students could barely read, write, or express their thoughts. “We have to learn how to think critically,” he said. “I’m talking about the here and now. I’m talking about what is said here.”

We already lived in a world of abundance, he impatiently explained to the pampered audience. The powerful refused to share the spoils. So why should they celebrate the wonders of digital connection? An artificially intelligent entity might seem interesting, even convincing as a digital companion, but it lacked the numinous qualities that make us human. “She was never a child,” Weizenbaum said. “She has no history.” His fellow panelists, in fact, reflected what he had been warning about for decades. “Everything we’ve talked about is threatening the image of mankind and what mankind is,” he said.

The moderator moved to interrupt. Weizenbaum went on, racing toward one of his favorite first-order concerns: “And then of course there’s the question, Do we need this?”

The moderator interrupted again. “No, I understand you are saying you don’t need it.”

Weizenbaum snapped back: “That’s all you understood?”

Witty, bitter, mocking from a place of well-earned expertise, it was a textbook Weizenbaum barb. The audience clapped briefly. And then they quickly moved on.

A computer isn’t “merely a tool,” Weizenbaum writes in Computer Power and Human Reason. “Tools shape man’s imaginative reconstruction of reality and therefore instruct man about his own identity.” He knew that computers were altering our perception of reality and of ourselves. If these machines deserved to be treated with any reverence, it was a fearful one. Weizenbaum’s colleagues went the other way: They chose awe, worshiping at the altar of computation, deciding that, through this new digital faith, anything was possible.

That, ultimately, may explain Joseph Weizenbaum’s continued obscurity, the deliberate obsolescence of his thought. He took aim at an industry and ideology that felt certain of its heroic techno-utopian future. He didn’t indulge in the supposedly revolutionary but ultimately conservative fantasies of his peers, not when experience and observation had shown that it was the regressive forces of consumerism, militarism, and corporatism that would set the direction of the computer age. His heresy was unwavering. He learned to say, “No!” Or, as Weizenbaum told his interviewer in Islands in the Cyberstream, “I stayed true to who I was.”