Claire Messud Writes Novels for a Different Century

Claire Messud’s best-known book, The Emperor’s Children, came out in 2006. It is the sort of best seller you don’t encounter as much these days, ponderous and churning with detail. Its characters are haughtily ambitious young people in early-aughts New York and the more successful adults they cling to, who have “vulpine” smiles and cluttered studies and positions of power in literary circles. The book’s vocabulary seems to be from another time: A hookup appears at the door with “a bristly dun tickler on his chin”; one character describes herself as “the uxorious type at heart.” Reading it now, it may occur to you that it was published the year before Apple released the first iPhone. Messud was writing for a readership with a prelapsarian attention span.

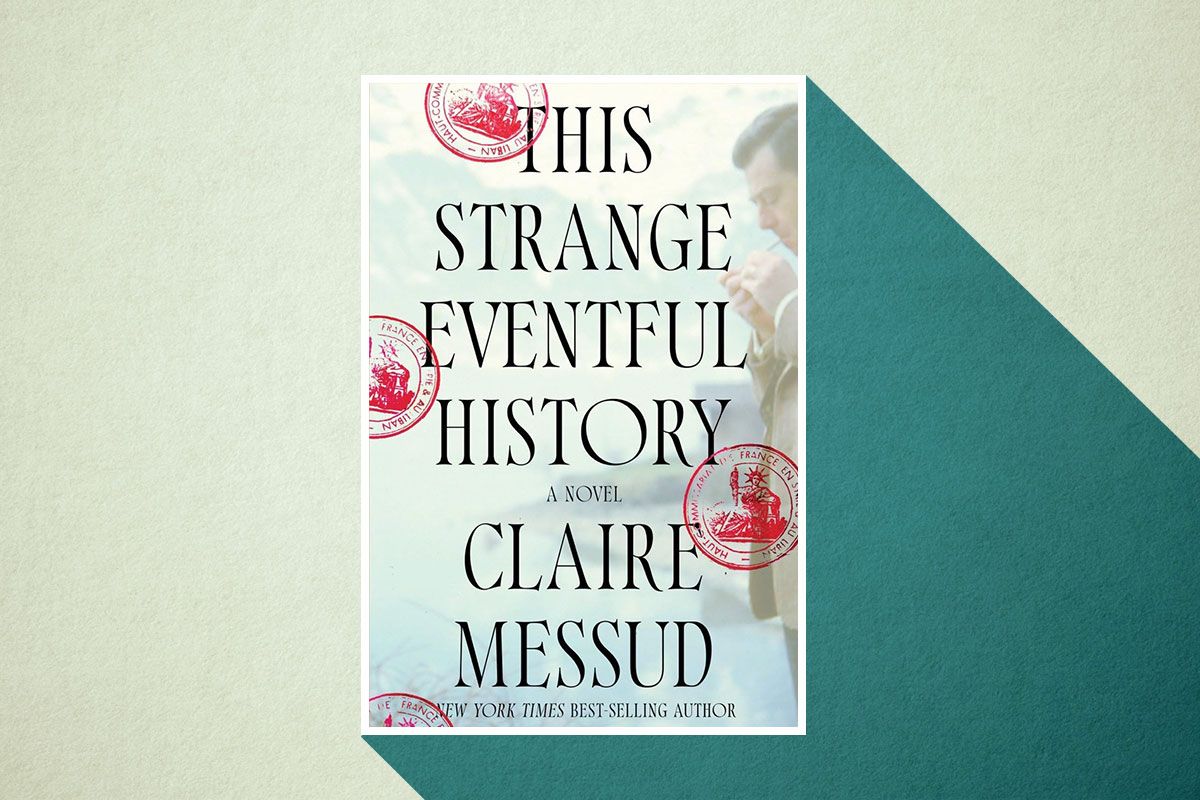

Messud, who is 57, might point that out too. On the subject of smartphones, she’s an alarmist. “In a way, I feel that of all the battles that we have, that is the biggest,” she said in 2020 on the author-interview podcast First Draft. “It’s a terrible diminution. The aficionados of computer life want to try to convince us that it’s better than real life, but it’s the death of two-thirds or three-quarters of our animal selves.” From her work — since 2006, she’s published two novels, a novella, and a memoir in essays, all favorably reviewed, but none best sellers in the same way as The Emperor’s Children — you get the sense that she spends much more time rereading Albert Camus than she does on any form of social media. Her fiction is not strictly anachronistic; her last novel, 2017’s The Burning Girl, is a wiry story about two teenage girls that captures the tenor of childhood under the internet. But the semi-autobiographical This Strange Eventful History, her seventh book of fiction now out this week, takes almost none of its cues from the language that exists on our screens. It’s a family story with the weighty tone and generation-spanning structure that used to signify an Important Novel. But does anyone want to read a good old-fashioned book these days?

Of course, the big family novel hasn’t exactly gone away. In the past couple of years, we’ve had the best-selling, Oprah-endorsed The Covenant of Water, by Abraham Verghese; Tommy Orange’s Wandering Stars, the subject of much critical attention; and the Booker-nominated The Bee Sting, by Paul Murray. In the world of popular literary fiction, though, This Strange Eventful History can feel incongruous: more acerbic than the typical book-club pick, but without the overt stylish newness of a punctuation-light novel like Murray’s.

And though Messud does seem to appear, as “Chloe,” in her new book, it is far from the airy world of autofiction. Rather than that genre’s sidelong irony and everyday language, which lets you slip in and out as though checking on a text chain, it is earnest, rigorous, and indebted to modernists like James Joyce and Virginia Woolf; you could call it a professor’s novel (she teaches at Harvard). She seems aware of the downsides of her approach. “In our age of rapid technology and the jolly, undiscriminating ephemeralizing of culture and knowledge,” she wrote in a 2011 essay on Teju Cole, “an insistence upon high stakes — a desire to ask the big questions — can seem quaint, or passé, or simply a little embarrassing.” The big questions are here, about family and colonialism and grief. But the real promise of a 425-page family epic is that it will provide an emotional punch, too. On that, it delivers.

The characters at the center of This Strange Eventful History, the upper-middle-class Cassars, are pieds-noirs — people mainly of French descent who were born in French Algeria. When the novel begins, the Germans are marching into Paris and the family has been separated. Later, the dissolution of colonial rule in the early ’60s forces them to leave Algeria for good. The novel unfolds in chapters that hop from Cassar to Cassar as they shuffle through countries, careers, and marriages. For most of the book, they are scarily small against the fabric of their time: This is not one of those novels that gives its characters brushes with world-historical power. But Messud is expansive in her descriptions of their insignificance.

Messud has said that This Strange Eventful History is based in part on her aunt’s diaries and an unpublished 1,500-page memoir handwritten by her grandfather. The implication is that this is a generational project: the gradual unburying of a family consciousness (and, eventually, one final, mind-bending secret). These are not new subjects for the author. Her second novel, 1999’s The Last Life, follows another family of French Algerians who scatter across the globe, and 2006’s novella The Professor’s History is set at the caves of Dahra, the site of a horrific French colonial massacre of Algerians in 1845. But her new book is more literally biographical.

It isn’t a simplification to trace the lines between Messud family members and the characters who echo them: grandfather Gaston, a French naval attaché turned businessman, and his saintly wife, Lucienne; their two children, François and Denise; and, eventually, their daughter, who seems to be Claire — here called Chloe, who marries someone like her real-life husband, the book critic James Wood (in the book, he’s given the name of a former family dog). Like Gustave Flaubert, one of her literary heroes, Messud is in search of the mot juste; that the right word is very often used to describe the embarrassments and errors of her own family members, or their fictionalized stand-ins, is part of what makes this such a stingingly intimate read. “He was washed with shame for his desire, and shame for his shame,” François thinks at one point after failing to hire a prostitute in Cuba. Messud’s willingness to imagine the depths of her father’s self-disgust is both tender and shocking.

Algiers, Lucienne and Gaston tell their children early in the novel, is the most beautiful city on earth. Their attachment to it, like their pious belief in their marriage — “the great masterwork of his life,” Gaston thinks — is poignant but perverse. The idealized notion of that life before the interruptions of war and colonial expulsion is a family myth that has the power to disfigure the younger generation, who are crushed by the fact that they can’t access their supposed homeland or the easy happiness of their parents. By the 1960s, the Cassars are disjointed: Denise and her parents are in Buenos Aires, and Gaston has married a Canadian woman named Barbara. Later, they all move again, to Australia and Toulon and Connecticut, drawn away by illnesses and unglamorous jobs at multinational corporations.

Messud isn’t an explicitly political novelist. Her favorite principle about writing, which she brings up in almost every interview, may be Chekhov’s assertion that it isn’t his job to tell you why horse thieves are bad people; instead, he’s there to explain what this particular horse thief is like. The degrading effects of colonialism, though, are a preoccupation of hers. Later in the book, at a lunch in 1989, the author’s 22-year-old doppelgänger, Chloe, volunteers “that accepted truism that the French presence in Algeria had been fundamentally wrong,” but we hear her through her aunt’s panicked hostility: “Denise could feel her hands clenching, that strange detachment of rage.” If there is a straightforward moral argument in the book, it comes in an exquisite chapter narrated by the idealistic aspiring writer Chloe, the only character who gets the first-person treatment. On a ferry from Calais to Dover, hot off the argument with her aunt, she decides you can’t choose the cohort of people you share your time on earth with. History, she thinks, is largely experienced through “the trappings of grief and fear.” Humans tend to be inadequate in the face of it, anxious and defensive.

There are parts in the middle of This Strange Eventful History that read syrupy slow, and it’s impossible not to catch some of the characters’ weariness and sadness. I felt the reader’s version of museum fatigue. Then, in its grim final third, as the older characters age and die one by one, it becomes a story about grief.

But in Messud style, familiar from the tart judgments of her characters in The Emperor’s Children, it can be very funny. She’s at her best in the omniscient third person, when we get to watch her characters’ patterns of thought. As they trade chapters, the Cassars mull over their private grudges. Barbara, François thinks, has a “snarky Canadian superiority.” She, in turn, thinks her father-in-law Gaston’s habit of calling his wife a “lay saint” is repulsive. And Denise, who’s intensely, hilariously neurotic all the way through her life, thinks of herself as self-sacrificial but is resented by almost everyone. Few books have captured how invasive it can feel to be part of a family, how embarrassing it is to have your life assessed by your sibling or your child — or, worse, by their wife. There’s a strain of cynicism and aggression that works like a counterbalance to the book’s central piety: that a life lived in service of art could fix some of this darkness, raining long-withheld empathy and understanding on everyone.

The idea that literature itself can offer absolution may be as quaint and passé these days as the Great American Novel, but Messud’s steady belief in it is intoxicating. “Literary language is a kind of spell,” she writes in the introduction of her 2020 essay collection. Similar to one character’s “beautiful French, like his cravat, somewhat old-fashioned, but so elegant,” her style comes to seem like a purposeful constraint. This Strange Eventful History might use some old tricks, but it’s hard not to be hypnotized.