Raman to go

For a harried wastewater manager, a commercial farmer, a factory owner, or anyone who might want to analyze dozens of water samples, and fast, it sounds almost miraculous. Light beamed from a central laser zips along fiber-optic cables and hits one of dozens of probes waiting at the edge of a field, or at the mouth of a sewage outflow, or wherever it’s needed. In turn, these probes return nearly instant chemical analysis of the water and its contaminants—fertilizer concentration, pesticides, even microplastics. No need to walk around taking samples by hand, or wait days for results from a lab.

This networked system of pen-size probes is the brainchild of Nili Persits, a final-year doctoral candidate in electrical engineering at MIT. Persits, who sports a collection of tattoos and a head of bouncy curls, seems to radiate energy, much like the powerful lasers she works with. She hopes that her work to develop a highly sensitive probe will help a technology known as Raman spectroscopy step beyond the rarefied realm of laboratory settings and out into the real world. These spectrometers—which use a blast of laser light to analyze an object’s chemical makeup—have proved their utility in fields ranging from medical research to art restoration, but they come with frustrating drawbacks.

In a cluttered room full of dangling cables and winking devices in MIT’s Building 26, it’s easy to see the problem. A line of brushed-aluminum boxes stretching eight or so feet across a table makes up the conventional Raman spectrometer. It costs at minimum $70,000—in some cases, more than twice that amount—and the vibration-damping table it sits on adds another $15,000 to the tab. Even now, after six years of practice, it takes Persits most of a day to set it up and calibrate it before she can begin to analyze anything. “It’s so bulky, so expensive, so limited,” she says. “You can’t take it anywhere.”

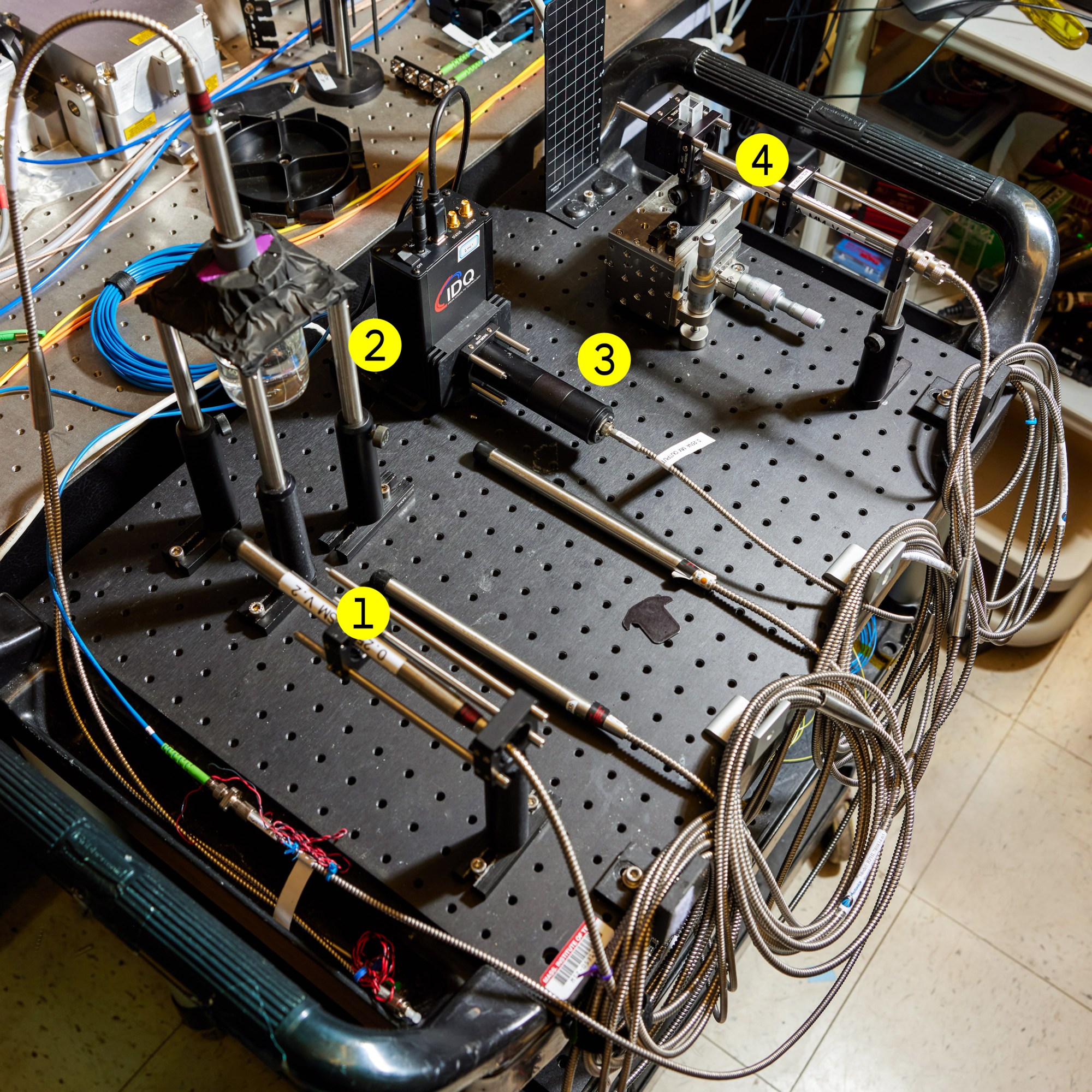

Elsewhere in the lab, two other devices hint at the future of Raman spectroscopy. The first is a system about the size of a desk. Although this version is too big and too sensitive to be moved, it can support up to 100 probes connected to it by fiber-optic cables, making it possible to analyze samples kilometers away.

The typical Raman system is “so bulky, so expensive, so limited. You can’t take it anywhere.”

The second is a truly portable Raman device, a laser about the size and shape of a Wi-Fi router, with just one probe and a cell-phone-size photodetector (a device that converts photons into electrical signals) attached. While other portable Raman systems do exist, Persits says their resolution and sensitivity leave a lot to be desired. And this one delivers results on par with those of bigger and pricier versions, she says. Whereas the bigger device is intended for large-scale operations such as chemical manufacturing facilities or wastewater monitoring, this one is suited for smaller uses such as medical studies.

Persits has spent the last several years perfecting these devices and their attached probes, designing them to be easy to use and more affordable than traditional Raman systems. This new technology, she says, “could be used for so many different applications that Raman wasn’t really a possibility for before.”

A molecular photograph with a hefty price tag

All Raman spectrometers, big or small, take advantage of a quirk in the way that light behaves. If you shine a red laser at a wall, you’ll see a red dot. Of the photons that bounce off the wall and hit your retina, nearly all of them remain red. But for a precious few photons—one in 100 million—something strange happens. The springlike molecular bonds of the materials in the wall jangle the photon, which absorbs or loses energy on the rebound. This changes its wavelength, thereby changing its color. The color change corresponds to whatever type of molecule the photon collided with, whether it’s the polymers in the wall’s latex paint or the pigments that create its hue.

This phenomenon, called Raman scattering, is happening right now, all around you. But you can’t see this color-shifted photon confetti—it’s far too faint, so looking for it is like trying to see a distant star on a sunny day.

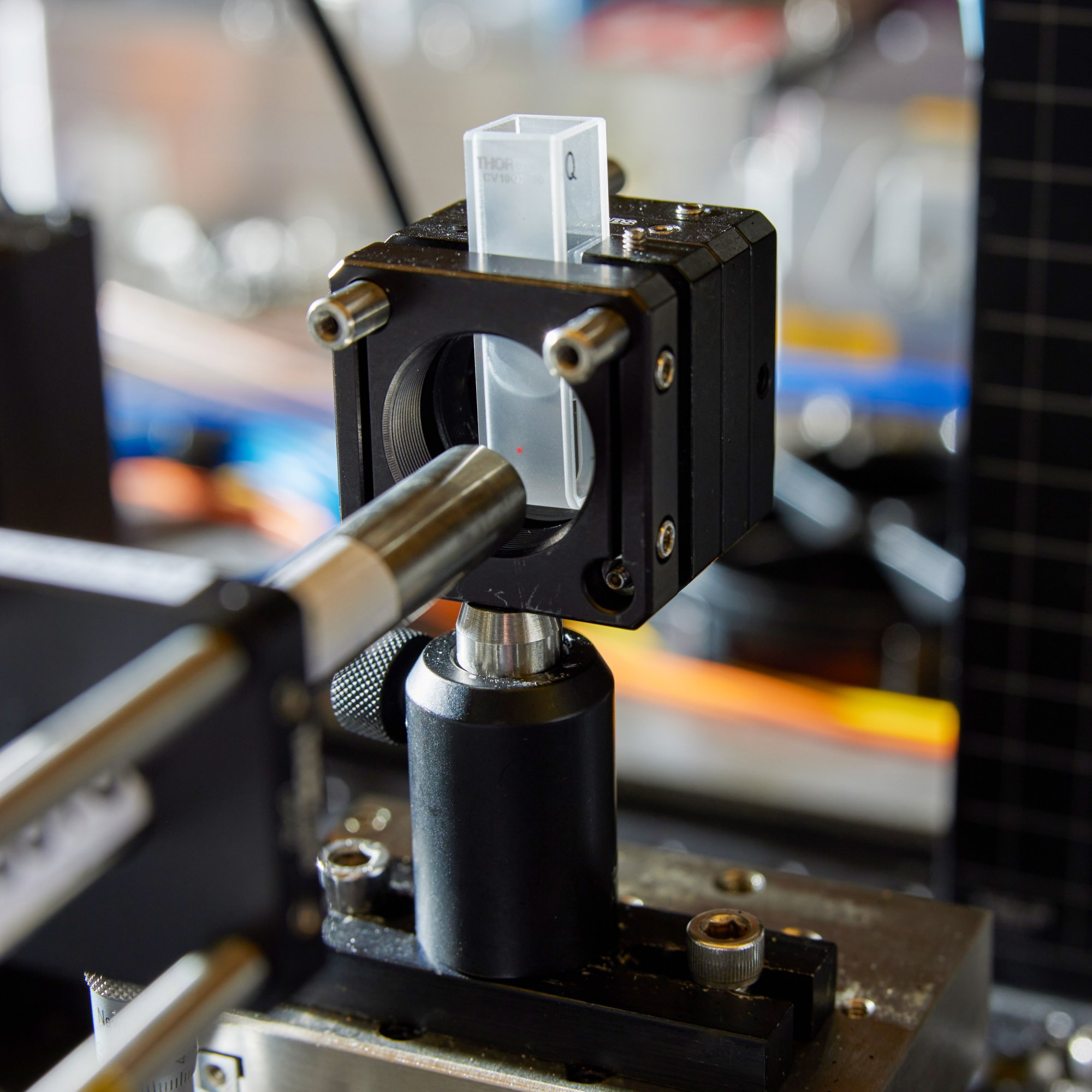

A traditional Raman spectrometer separates out this faint signal by guiding it through an obstacle course of mirrors, lenses, and filters. After the light of a powerful, single-color laser is beamed at a sample, the scattered light is directed through a filter to remove the returning photons that retained their original hue. The color-shifted photons then go through a diffraction grating—a series of prisms—that separates them by color before they hit a detector that measures their wavelength and intensity. This detector, Persits says, is essentially the same as a digital camera’s light sensor.

1. A mounted probe can be used to study non-liquid, uncontained samples like plants.

2. A probe encased in a protective sleeve is immersed in a liquid sample.

3. An optical receiver detects Raman photons collected by a probe and relayed by a fiber-optic cable.

4. A probe to measure small-volume liquids in a cuvette.

At the end of the spectroscopy process, a researcher is left with something akin to a photograph—not of an object’s appearance, but of its molecular makeup. This allows researchers to study the chemical components of DNA, detect contaminants in food, or figure out if an antique painting is authentic or a modern counterfeit, among many other uses. What’s more, Raman spectroscopy makes it possible to analyze samples without grinding them up, dissolving them, or dousing them in chemicals.

“The problem with spectrometers is that they have this intrinsic trade-off,” Persits says. The more light that goes into the spectrometer itself—specifically, into the color-separating diffraction grating and the detector—the harder it is to separate photons by wavelength, lowering the resolution of the resulting chemical snapshot. And because Raman light is so weak, researchers like Persits need to gather as much of it as possible, particularly when they’re searching for chemicals that occur in minute concentrations. One way to do this is to make the detector much bigger—even room-size, in the case of astrophysics applications. This, however, makes the setup “exponentially more expensive,” she says.

Raman spectroscopy on the go

In 2013, Persits had bigger things to worry about than errant photons and unwieldy spectrometers. She was living in Tel Aviv with her husband, Lev, and their one-year-old daughter. She’d been working in R&D at a government defense agency—an easy, predictable job she describes as “engineering death”—when a thyroid cancer diagnosis ground her life to a halt.

As Persits recovered from two surgeries and radiation therapy, she had time to take stock of her life. She resolved to complete her stalled master’s degree and, once that was done, begin a PhD program. Her husband encouraged her to apply beyond Israel, to the best institutions in the United States. In 2017, when her MIT acceptance letter arrived, it was a shock to Persits, but not to her husband. “That man has patience,” she says with a laugh, recalling Lev’s unflagging support. “He believes in me more than me.”

The family moved to Massachusetts that fall, and soon after, Persits joined the research group of Rajeev Ram, a professor of electrical engineering who specializes in photonics and electronics. “I’m looking for people who are willing to take risks and work on a new area,” Ram says. He saw particular promise in Persits’s keen interest in research outside her sphere of expertise. He put her to work learning the ins and outs of Raman spectroscopy, beginning with a project to analyze the metabolic components of blood plasma.

“The first couple of years were pretty stressful,” Persits says. In 2016, she and her husband had welcomed their second child, another girl, making the pressures of grad school even more acute. The night before her quantum mechanics exam, she recalls, she was awake until 3 a.m. with a vomiting child. On another occasion, a sprinkler in the lab malfunctioned, ruining the Raman spectrometer she’d inherited from a past student.

“We can have real-time assessment of what’s going on. Are our plants happy?”

Persits persevered, and things started to settle into place. She began to build on the earlier work of Ram and optical engineer Amir Atabaki, a former postdoc in the Ram lab who is now a research fellow at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California. Atabaki had figured out a fix for that fundamental Raman trade-off—the brighter the light, the lower the resolution of the chemical snapshot—by using a tunable laser that emits a range of different colors, instead of a fixed laser limited to a single hue. Persits compares the process to photographing a rainbow. A traditional Raman spectrometer is like a camera that takes a picture of all the rainbow’s colors simultaneously; the updated system, in contrast, takes snapshots of only one color at a time.

This tunable laser eliminates the need for the bulkiest, costliest parts of a Raman spectrometer—those that diffract light and collect it in a photon-gathering sensor. This makes it possible to use miniaturized and “very simple” silicon photodetectors, Persits says, which “cost nothing” compared with the standard detectors.

Persits’s key innovation was an exceptionally sensitive probe that’s the size of a large marker and is connected to the laser via a fiber-optic cable. These cables can be as long (even kilometers long) or short as needed. Armed with a tunable laser, simple photodetectors, and her robust, internet-enabled probes, Persits was able to develop both her handheld Raman device and the larger, nonportable version. This second system is more expensive, with a vibration-damping table needed for its sensitive laser, but it can support dozens of different probes, in essence offering multiple Raman systems for the price of one. It also has a much broader spectral range, allowing it to distinguish a greater variety of chemicals.

These probes open up a remarkable host of possibilities. Take biologics, a class of drugs generated by genetically engineered cells, which account for more than half of all modern cancer treatments. For drug manufacturers, it’s important to make sure these cells are happy, healthy, and producing the desired compounds. But the mere act of checking in on them—cracking open the bioreactors in which they grow to remove a sample—stresses them out and introduces the risk of contamination. Persits’s probes can be left in vessels to monitor how much the cells are eating and what chemicals they’re secreting, all without any disturbance.

Persits is particularly excited about the technology’s potential to simplify water monitoring. First, though, she and her team had to make sure that water testing was even feasible. “A lot of techniques don’t work in water,” she says. Last summer, an experiment with hydroponic bok choy proved the technology’s mettle. The team could watch, day by day, as the plants sucked up circulating nitrate fertilizer until none remained in the water. “We can actually have real-time assessment of what’s going on,” Persits says. “Are our plants happy? Are they getting enough nutrients?”

In the future, this may allow for precision dosing of fertilizers on large commercial farms, saving farmers money and reducing the hazardous runoff of nitrates into local waterways. The technology can also be adapted for a range of other watery uses, such as monitoring chemical leakage from factories and refineries or searching for microplastics and other pollutants in drinking water.

With graduation at the end of May, Persits has set her sights on the next phase of her career. Last year, funding and support from the Activate fellowship helped her launch her own company, Dottir Labs. Dottir—which stands for “digital optical technology” and also alludes to her two daughters, now 12 and eight—aims to bring her Raman systems to market. “Dottir is really focusing on the larger-scale applications where there are few alternatives to this type of chemical sensing,” Persits says.

Like the subject of one of her tattoos, which shows a lotus growing from desert ground, Persits’s research career has been defined by surprising transformation—photons that change color after a glancing blow, bulky machines that she shrank down and supplemented with a web of probes. These transformations could nudge the world in a new direction as well, leading to cleaner water, safer drugs, and a healthier environment for all of us downstream.