What Happens When a 5.9 Climber Starts Training Like a Pro?

This story originally appeared in the February 2016 issue of our print edition and is reproduced here for free. Sign up with a Climbing membership, now just $2 a month for a limited time, and you get unlimited access to thousands of stories and articles by world-class authors on climbing.com plus a print subscription to Climbing and our annual coffee-table edition of Ascent. Please join the Climbing team today.

“I should feel some muscle here, but there’s nothing,” said Kris Peters as he squeezed my rotator cuff and looked me up and down like a judge would a state fair cow. “And I can tell your fingers are going to be a weak link just by looking at them. We’re going to spend a lot of time on those.”

I’d just come to Movement Climbing + Fitness, a couple blocks away from my Boulder, Colorado apartment, for my first meeting with Justen Sjong and Kris Peters, a coaching and training duo formerly working together as Team of 2 (Sjong is now the senior director of route setting and programs at El Cap Climbing Yoga and Fitness). Their assessment of my potential began, unbeknownst to me, as soon as I walked in the door. My physical attributes adequately scrutinized, Sjong noted that my body language suggested I was timid and reserved. Not ideal for coaching. All this in the first five minutes. I was about ready to quit climbing forever and go put a buffet out of business.

But this unbiased assessment is why I’m here. I’ve never been a good rock climber. After five years at the sport, I still found myself getting sketched leading 5.9 sport routes outside and failing on V3 boulder problems in the gym. It’s not for lack of trying, though. I’ve gone through periods where I’d pull plastic four days every week. I’ve taken classes on technique. I’ve read nearly every book on training and put in my time doing pull-ups, deadhangs, and planks. But my anarchic, inconsistent routine seemed to be getting me nowhere. At 30 years old I’d plateaued at average, so I began wondering: What if I got serious about climbing? Like really serious. Not just scanning the gym for the newest 5.10 to try, but truly giving it everything I had. What if I trained like a pro? I decided to seek the help of the same people who work with Daniel Woods and Alex Puccio, dedicate myself to their program, and see how far I could get. The goal: redpoint a 5.11 outside in two months. But first, we’d have to find my missing shoulder muscles.

Read More: Learn to Train: The Complete Guide to Training for Climbing

Redefining Goals

My first session was an assessment with Sjong (an official one this time). We’d spend two hours in the gym poring over my strengths and weaknesses to inform the next two months of training. Sjong would serve as my coach. He was in charge of my movement and mental game. I went in a bit cocky. I knew I was a physically weak climber, and I believed that I compensated with good technique. Where my friends would muscle up boulder problems in ways I could only dream about, I’d find nuanced positions that avoided the need for strength. Sjong obliterated that theory.

Ask an expert… Should you just climb more? Justen Sjong: No. Once you know how to rock climb, climbing becomes obsolete to training. Training becomes very task-oriented. What are your needs? And how are you working toward achieving them?

The lessons started during our warm-up, and they never stopped. Nearly everything Sjong says is eye-opening and brilliant. He changes your entire perspective on climbing technique five times per session. He is indeed, a sensei. A master of the climbing arts. He led me into his first piece of enlightenment with a question.

“What do you think footwork is?”

“Using your legs to move your body up the wall?”

“Incorrect. Your knees move your body up and down. Your feet and your toes manage your hips.”

He elaborated: You can use your toes to pull your hips into the wall. You can pivot your feet to swing your hips into a different position. Our hips are roughly our center of gravity. Our center of gravity controls our balance. Balance is everything. Our feet control everything. And I’d already demonstrated poor footwork. Sjong noticed that I’d been dropping my feet onto holds, not placing them deliberately. And I’d been standing on the meat of my feet, not my toes. Our toes, like our fingers, can get stronger, but only if we use them. And by not using them I was obstructing my ability to pivot my hips.

Sjong is undoubtedly a brilliant climber, his most major claims to fame being the first free ascents of The PreMuir (5.13c/d) and Magic Mushroom (5.14) on El Cap. But his uncanny talent for observation is what makes him such a brilliant coach.

Ask an expert… Should you stretch? Kris Peters: Absolutely. Foam rolling and stretching after every session is really good. It’s a boring thing to do, but keeping yourself loose is a great thing to add for 20 to 30 minutes every other day or after each workout.

“It’s who I am. I’m an observer.” Sjong says. “I don’t like going to parties, but if I do I’m that guy that hangs out in the back and watches people. Body language is more true and honest than what comes out of your mouth.”

The biggest thing Justen observes during our session is that I like to be in control. Balance is good, but control is bad. Balance is about finding a comfortable position on the wall. Control is more akin to leaving a foot on a hold during a big reach, when it would be more efficient to make the move without three points of contact. It also leads me to scrunch up when I start to get gripped. I pull myself into the wall tight to stay solid, when really I’m just tiring myself out faster. Sjong says that this is a common problem, one he himself struggled with.

“My wife noticed that she could always tell when I was going to fall,” he said. “I’d bunch up and jack my feet up. It was a sign that I couldn’t deal with the situation. I realized that if I could self-identify that moment early, I could correct course and create a better outcome.”

My vision of myself as a brilliant technical climber was blown apart in the first hour, but that’s exactly what I was hoping for. If I were good at identifying my own weaknesses, I would’ve addressed them long ago. I left the session with sore fingers, but feeling great. We concluded by redefining my goal.

“Leading 5.11a isn’t a goal. It’s an outcome,” Sjong said. “The goal is to address your weaknesses. If we are successful, the outcome will be climbing 5.11a. You can achieve the outcome without reaching your goals or vice versa, but you’ll grow more as a climber in the long term if you achieve your goals.”

I would need to improve more than my technique if I was going to achieve my goals.

Read More: Learn to Train for Rock Climbing: Improve Your Climbing Technique

Starting Strength

My first session with Peters was a different kind of learning experience. Peters is a personal trainer. He had one job: to make me strong. He came from a more traditional sports background, playing college basketball and dreaming of working with NFL players. Like me, he discovered climbing in his 20s then moved out to Boulder to pursue it. I went in a bit nervous. Peters had warned me that he likes to yell. I was expecting an aggro football-coach type. Instead, his “yelling” is positive and motivating. It’s like he’s raising his voice to tell you that he believes in you. It’s nice.

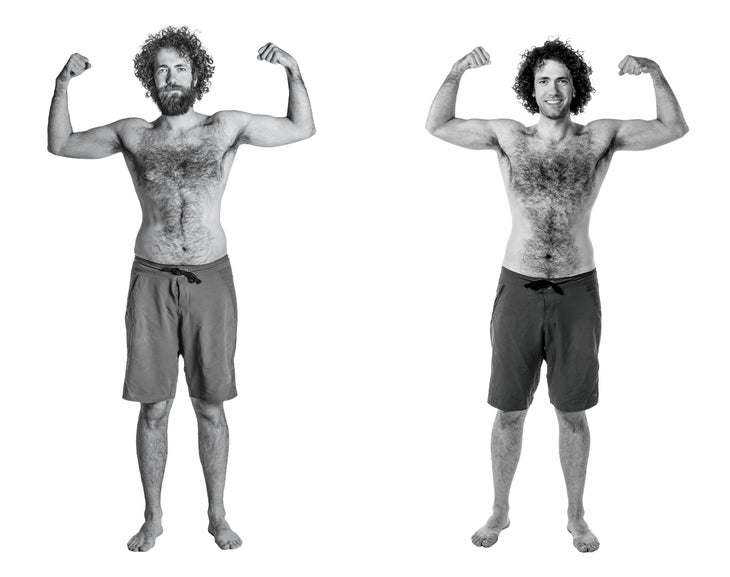

But that doesn’t mean his sessions are easy. Through some rounds on the steep bouldering wall and time in the weight room doing pull-ups, pushups, and various other exercises, we confirmed what I had long suspected: I am not strong.

“Most climbers mistakenly think they need stronger fingers, when they’re actually failing with technique or other factors,” Peters said. “You actually do need stronger fingers.”

Ask an expert… Should you take rest days? Kris Peters: Rest days are crucial. Even if you feel good, it’s still important to take a rest day. Your body needs to recover. Over time it catches up with you if you don’t take them. People get hit with overtraining over time. They just end up tired and fatigued. I always say, if you feel good and don’t want to take one, do an active rest day. Go for a bike ride or a hike. Don’t do anything really intense. For most of my training plans I include two rest days totally off per week.

The official written assessment identified areas that needed work: upper body, core, biceps, shoulders, forearms, and hand and finger strength (this one accented with asterisks and exclamation points). It also noted that shoulder strength was a huge need, and that my shoulders would blow out if not addressed. If you zoned out during that list, I’ll summarize: Everything above my waist needed serious work.

Read More: “The Proven Way to Get Stronger Fingers”

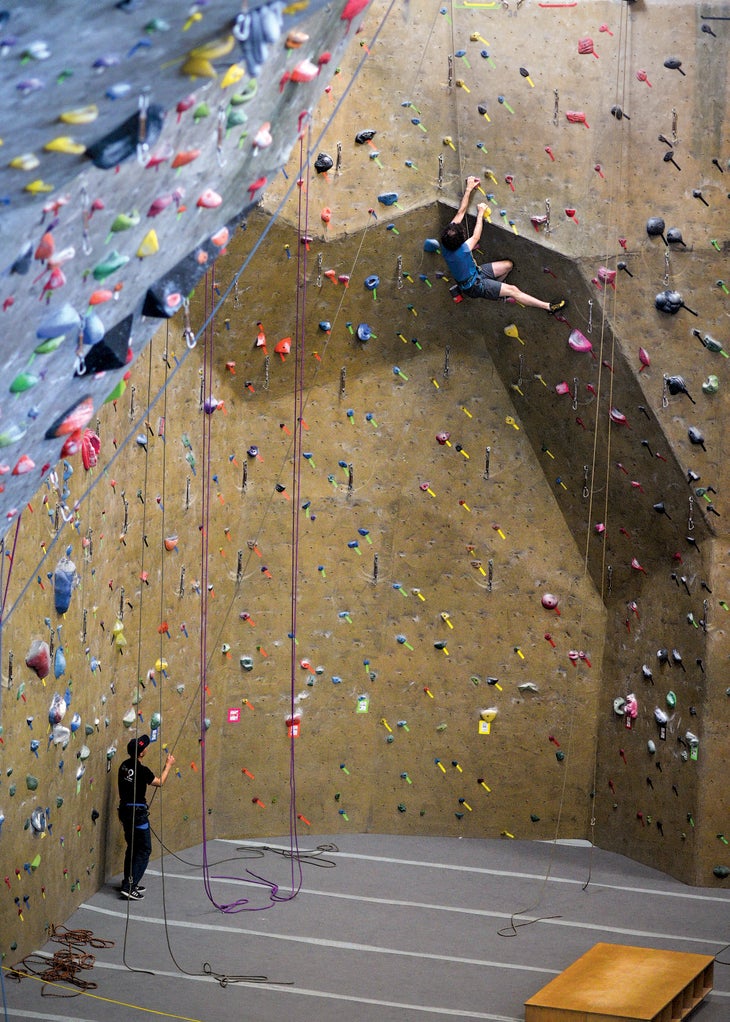

My weaknesses noted, I hit the gym. Nearly every day. I’d meet with Sjong and Peters every other week. The rest of the time I’d be following a plan they designed. My routine would be five days a week, granting me rest days on Monday and Thursday. It was a combination of climbing, strength training, and injury prevention exercises. These were not short workouts. After a full day at the office, I’d head to Movement and spend three to four hours climbing and lifting weights. To add to the difficulty, Peters had imposed a rule. I was not allowed to climb anything vertical or less. Only steeps and ceilings from here on out. Steeps would make me strong. I noted in my diary, “Shit’s about to get a lot harder.”

The Missing Link

I was pushing myself to the limit, but still missing a crucial piece of the puzzle. By the end of the second week I was losing weight. I was feeling weak. I’d get frequent bouts of lightheadedness. I wasn’t sleeping. I was turning into a grumpy asshole. During one training session my vision blurred out and I nearly fainted after just 10 minutes of moderate jogging on the treadmill. I’d even picked up a cold. These are all classic signs of overtraining, and it was happening because I wasn’t providing my body with the fuel it needed to work hard.

The solution? An older issue of this very magazine. While reading an article about over-gripping, I noticed the byline: “As a certified sports nutritionist (MS, CISSN), Brian Rigby works with climbers and other athletes at Boulder’s Elite Sports Nutrition in Colorado.” Boom. I emailed him and asked for a consultation.

Read More: “Dieting for Climbing? Here are Four Things You Should Know” by Brian Rigby

Rigby was psyched about the project and extremely psyched about nutrition. It’s clear the subject extends beyond a mere professional interest for him. This is a man who spends his waking hours poring over research papers to learn everything he can about his chosen subject. Rigby took fat readings with an ultrasound device (19%, average) and presented my plan. I was expecting him to tell me how many pounds of kale I’d have to eat each day and give me a weight loss goal. It was actually much simpler. There were no specific foods, just daily macronutrient goals and a few supplements.

“I typically don’t make meal plans,” Rigby said. “Athletes are healthy people by and large. They know how to cook, or how to make good choices when they eat out. They just need tweaking. There’s a difference between eating right and eating right for an athlete.”

The goal of my plan was to provide me with sufficient energy to complete all of my workouts and maximize their benefit. Even though I could stand to drop a few pounds, I would be trying not to lose weight. Ideally, I would finish the two months at the exact same weight I started.

“Some climbers enter this eternal cycle, where they’re always trying to maintain their weight or lose weight,” Rigby said. “They’re never putting in the extra calories they need to gain strength. And if you’re not gaining strength you will hit a plateau.”

I went home and looked up the supplements Rigby had recommended (see Climbing Supplements sidebar below). I was delighted to find an Amazon review of Citrulline Malate that read, “Gives me insane pumps and vascularity, and as an added bonus gives you incredibly hard erections when you are getting into it with the ladies.” If it could help this horny fellow’s performance in the bedroom, surely it would help me on the wall.

Ask an expert… Should you do cardio? Kris Peters: Any athlete can benefit from conditioning, just being physically fit. It adds to your recovery, your confidence, your physique. I don’t say that if you bike, run, or swim you’re gonna climb three grades harder. We do have some climbers who want to lose weight and we tell them that they gotta do more cardio.

It was around this time that I made an important mental shift. I decided to start thinking of myself as an athlete. I don’t know what I thought I was before. Rock climbing enthusiast? Truthfully, I didn’t feel anyone would take me seriously if I called myself an athlete. I don’t have a flat stomach. I don’t have big muscles. One time at a Mexican restaurant I tried to order by telling the waitress, “I’ll have the most fat-person food on the menu.” When she didn’t understand, I asked which dish had the most meat and cheese. But calling myself an athlete wouldn’t be about what other people thought. It was about recognizing that my decisions have an effect on my performance in my chosen sport: climbing. It would mean not skipping workouts. It would mean pushing myself hard. It would mean allowing myself to believe that I do have what it takes to climb better. And yes, not ordering food by its cheddar-to-beef ratio. It felt like an important moment.

I arrived at my second session with Sjong in time to see him finishing up with his previous client, Alex Puccio. I felt cool as hell. My coach was going right from working with Alex Puccio to working with me (the opposite of Alex Puccio). This session wasn’t littered with truth bombs like the last, but it was a confidence builder. I was starting to feel really good about my progress, but I’d soon find that the two months would be more like a rollercoaster than an elevator.

Ups and Downs

On March 19, I wrote in my training diary: “I’m starting to see the effects of this intense training on other parts of my life. I always wish I had more time to sleep in the morning, despite getting nine hours every night. My kitchen is a fucking nightmare. My slow cooker has been sitting on the counter with chicken breast pieces in the bottom for two days because there’s not enough room in the sink to clean it. Most of my waking hours are consumed by work, training, and keeping my diet in order. You really have to give it your all to train like this. I now understand what it means to be dedicated.”

On March 20, I noted that I could feel my upper abs under my belly fat, and they felt solid. I headed to Clear Creek Canyon and led my hardest sport route to date: Herbal Essence (5.9+) at Little Eiger.

All this time I’d been striving to train like a pro climber, but what did that actually look like? I reached out to Puccio, and she agreed to let me observe one of her sessions with Sjong. I was expecting to see a Terminator-like climbing machine. Instead, Puccio was surprisingly human. She did warm up on the hardest problems in the gym, but she would also get frustrated at times. She complained when Justen made her jump rope. I wondered, why does one of the strongest climbers in the world even need a coach?

“I know how to train myself, but I needed to get better mentally. That was my weakness,” Puccio said. “The tricky part is finding a coach that works well with you. Justen has a really good mental strategy and approach. The way he climbs is really controlled. Very intuitive. I really trust his opinion, and I think my mental approach is definitely a lot better now.”

“With Puccio, it’s just fucking with her,” Sjong said of his strategy. Not what I was expecting. “I fuck with her so she’ll lose her confidence. For a pro, it’s all headspace. They’re not technically moving incorrectly, but everyone loses their confidence. The champions know how to get it back.”

Ask an expert… Should you take vitamins? Brian Rigby: Multivitamins enjoy this aura of health, but there really isn’t any data to support their use. We have data from over 400,000 combined individuals, and they’ve never been able to show that multivitamins improve basically any outcome. Most people, when they think about nutritional requirements, don’t actually understand how we measure them. There are very few nutrients that the average American falls short on.

The week following Herbal Essence, Peters introduced the hangboard and the TRX straps into my training. I survived the hangboard. The TRX core routine I didn’t even come close to completing. Try this with your feet in TRX straps: one minute plank, one minute reverse crunches, one minute mountain climbers, another minute of planking, then finally a minute of oblique crunches. That’s all without resting. I bet you can’t do it. I couldn’t. I got through the first plank, then about 20 seconds of each subsequent exercise. I began to feel like I would never be strong. Strong was something the 20-year-old chiseled boulderers in the gym were and I was not—and would not be, ever.

I was starting to get overwhelmed. I decided to take a much-needed cheat day and climb the Second Flatiron and drink beer with my friend Dakota on what should have been a rest day. Dakota is the strongest climber I know personally. This year he took second place in the elite division at 24 Hours of Horseshoe Hell, climbing 185 (!) routes in a day. But ever humble, Dakota insists he’s nothing special. I asked what his current climbing goals were. He told me he wanted to get to the point where he could climb at the same level on any type of route, on any type of rock. He wanted to be well-rounded. I looked back at the work I was putting in. I hadn’t been jumping up the grades like I’d hoped, but I was definitely improving in less tangible ways. I was much more confident on the rock. I was dispatching routes within my range more quickly. I was reading sequences better. I began feeling better about my situation. Then we ate burgers and drank a bunch of beer, which also helped morale.

Ask an expert… Should you use a system board? Justen Sjong: More climbers should use the system board. It trains movement by rewiring the neurological pathways in our brain. It’s like dribbling practice for soccer or basketball. Every level should do it.

Peters announced that his goal for our next session was to destroy me completely. And that’s what he did. This time it was with a 4×4 with core work between each round. I would climb four problems on the steep bouldering wall, then head into the weight room for rapid-fire sets of planks and sit-ups. By the end of the session I was so pumped that I fell off a monster jug because I couldn’t bend my fingers anymore. They just stopped working. Mission complete. After Peters left, an older woman that had witnessed the ordeal asked me if I wanted her to shoot him. I said yes, please. But it was not to be. And I still had another round of core work to do. Here the challenge became not throwing up my sports drink on the mat. The plank position, with abs squeezed tight, is quite conducive to surprise barfs.

I was now halfway through the challenge. It was time for a nutrition follow-up. Things were going well, but I had some questions. The only way I’d found to hit my nutrition goals was to eat the exact same thing every day. I worried the lack of variety (mostly sweet potatoes, bananas, chicken breast, chocolate milk, and avocados) was depriving me of some necessary nutrients. Rigby was not concerned. If the repetition wasn’t driving me crazy, it wasn’t doing any harm. I also worried I was consuming too much sugar through my sports drinks, roughly 80g an hour during training to hit my carbohydrate goals. Rigby explained that the sugar was fuel I was transporting directly to my muscles. I should fail because I run out of muscle power, not because I run out of fuel. Our bodies can absorb up to 90g of carbs per hour, and that’s what would provide me with the most benefit during training.

Air Time

Another session with Sjong. I knew we’d cover lead falls eventually. It’s embarrassing to admit, but in five years of climbing I’d never taken an unplanned lead fall. I’d taken practice falls, sure, but I’d never tried hard and failed above a bolt. I started climbing in NYC, and the lack of access fostered an approach I call Vacation Climbing. My outdoor days were so limited that I’d only climb classics I knew I could finish. It wasn’t worth wasting my time on a route I might fail on. It turns out that’s not a good way to improve.

Falling came up on my second lead. I became hesitant to make an insecure clip in an awkward stance, and Sjong told me to take a fall. Instead, I downclimbed to the bolt below before weighting the rope. That didn’t fly. I had to take a fall. I climbed up and with much hesitation, let go… and it was fine. Sjong gave the best catch I’d ever had. It was like nothing happened. I decelerated slowly and comfortably into the air. Just experiencing such a great catch gave me more confidence on lead. Back on the ground I asked Sjong to show me his belay secrets.

“It’s a matter of letting the rope take you,” he said. “Don’t fight it, but don’t actively jump either. Just let it pull you from the hips and go with it.”

I used to believe that overcoming the fear of falling was a one-step process. I now see that it’s more nuanced. For me, climbing above a bolt indoors was a step. Then climbing above a bolt outdoors was a step. Then doing moves where my feet were out to the side while above a bolt indoors was a step. Then doing the same thing outside was a step. This was not something I could solve overnight.

Read More: “Want to Send Your Project? Try Fall Therapy” by Arno Ilgner

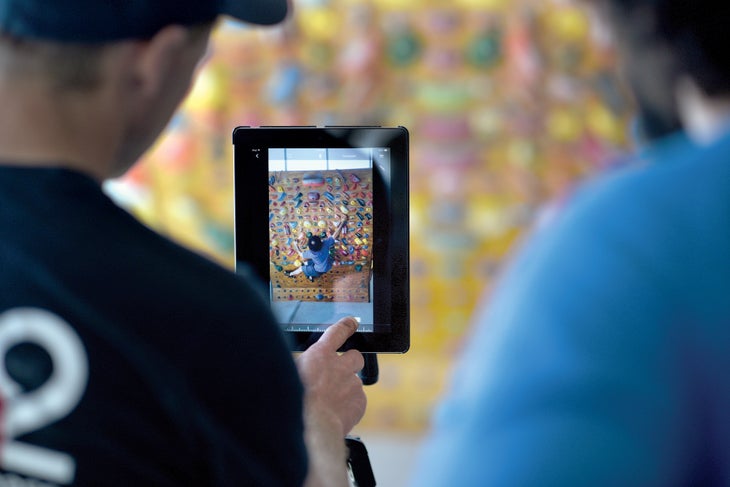

We move to the system board. Sjong films my attempts on an iPad, then shows me the footage in slow motion. We pinpoint the exact moments that lead to my failures. I need to point my toe to create core tension. I need to engage my breath. I need to sink down lower before launching into the move. Etc. I’m beginning to see that it’s all these little things that will make me a better climber. If I can put them all together, it will make for a big improvement. Strength training takes time. You can only do so much without getting injured. If I focus on each of these little things, I can make progress right now.

Ask an expert… Should you drink red wine? Brian Rigby: We can’t store the energy from alcohol; it’s just a toxic compound our body metabolizes. It’s not the end of the world, but there are no athletic benefits that I know of.

I hit a snag. During a trip to the grocery store to buy more almond milk and frozen kale for my daily lunch smoothie, I spot a new flavor of Ben & Jerry’s that contains a frozen core made entirely of crushed chocolate cookies. My heart skips a beat. I throw the pint in my cart. At home, the gravity of the situation sinks in. I simply can’t eat this cookie orgasm on my diet. All I’ve done is bought a loaded gun for my freezer. It will sit there through the rest of the challenge, tempting me every time I pull out a bag of frozen berry medley. I must be strong.

I dreaded my next session with Sjong because I knew what was coming. I was going to have to take a big fall. And I did, but not how I expected.

We spent the session doing triples. I would climb a route. Then climb it again. And again. The goal was to improve with each attempt. Sjong didn’t encourage me to fall. In fact, he preferred I take at a bolt if needed and send each section cleanly. The big moment came on a 5.10b with a roof.

I started by toproping the route twice. I made it through OK, but struggled a bit on the handful of moves that went up the roof. I had to rush through them without stopping. I worried about completing it on lead.

By this point I’d chosen my goal route: Free Willy (5.11a) in Boulder Canyon. I told Sjong. He remembered it vividly and gave me some tips on how to project it.

Ask an expert… Should you take anti-inflammatory pills? Brian Rigby: I recommend against anti-inflammatories in general because they’ve found that anti-inflammatories, particularly Ibuprofen, inhibit the natural healing process and the muscle growth process. Look at antioxidants. We used to think they sped up recovery time, but what we’ve found is that they’re actually decreasing training adaptations. Inflammation is a natural stage of training adaptations.

“Break the route up into sections. Climb up to the first crux, lower, repeat. Continue the process for each section of the climb,” he said. “Lower slowly and brush the holds on the way down to lock them into your memory. You should count every individual move. When you’re lying in bed at night, you should be able to rehearse them in your head, remembering each number exactly. You need to have it memorized.”

Next I led the 10b three times. The first two runs went well. I had to hang below the roof each time, but I fired off the crux sequence clean. Sjong assumed I was pretty tired by the third attempt. He only wanted me to climb as well as I did on attempt two. I felt I had the route wired and was determined to redpoint it. An important thing happened at the crux. I was above the bolt, and I needed to reach the next handhold to make the next clip. In order to do that, I had to get a high foot, but I was too pumped to lock off and get in position. I fumbled my foot onto a lower hold and eyed my target. Sjong yelled for me to get my foot higher, but it felt impossible. I realized that if I went for it I was probably going to take an unplanned fall, but there was also a chance that I’d make it. In the past I’d always been too timid to go for it in these situations. Now I was so determined to get to the top that I felt no fear. I launched my body toward the marginal handhold and whiffed a full 6 inches short, falling into space. I was ecstatic. This was my first unplanned lead fall. It wasn’t scary. It wasn’t jarring. It was actually fun. On the ground, I told Sjong how proud I was to have gone for the move even though I might fall.

“You went for the move even though you were definitely going to fall,” he countered. “There is honor in going for a high point and falling, but no honor in falling because you couldn’t get your foot up and went for it anyway.”

Fair enough. It was still a victory on the psychological front. Sjong said I needed to lead more, inside and outside. He suggested I lead routes over and over to build my confidence. A route isn’t done because we get to the chains. We should climb routes multiple times, striving to make each send better than the last.

Outcomes

It was at this point, three-quarters of the way through the two-month plan, that I started seeing rapid improvement. At the beginning I’d struggle on some of the gym’s V2s. Suddenly I was onsighting V3 and sending the occasional V4. I finally pieced together some of the longer roof problems I’d been projecting in the cave. I was feeling strong. It was time to attempt Free Willy.

Read More: “How to Get Stronger? Turn Climbing into Training” by Jonathan Siegrist

One faithful weekend I headed out to Animal World in Boulder Canyon. A friend put a toprope on Free Willy so I could work the moves. It took some time, but I climbed through the lower crux. It shed light on what 5.11 climbing feels like. I had to pull against shallow double cracks with just the tips of my fingers as I pressed up on miniscule crystals and smears with my feet. But I did it. And I felt like I could do it again. The whole route was actually going pretty well until I reached the traverse. Free Willy finishes with a nice no-hands rest that leads into roughly 12 feet of traversing on pumpy jugs followed by the namesake move, an awkward beached-whale flop up onto a ledge. I had two problems. First, I was pumped beyond belief. I didn’t have enough juice to climb through the traverse in one go. The second problem was that the rope wasn’t running through any directionals. If I fell, which I was confident I would, I would be dealing with a pretty nasty swing. I clipped the nearest draw and lowered, simultaneously motivated and defeated. I wasn’t ready for the redpoint burn, but it was in the foreseeable future.

I visited Rigby one last time to assess my physical progress. I was now 182 lbs., about what we’d hoped. And despite gaining a pound, my frame was leaner and firmer. With the help of the ultrasound, we determined that I’d lost one pound of fat and gained two pounds of muscle. My girlfriend confirmed this by telling me how great my shoulders looked. There was now something to grab.

Ask an expert… Should you eat organic? Brian Rigby: When we look at an organic bag of frozen broccoli versus a regular bag of frozen broccoli, organic is virtually meaningless. It doesn’t have a higher amount of nutrients in it. And there’s literally no scientific evidence at all that pesticide residues are harmful to humans in the amounts we are eating them.

When all was said and done, I asked Sjong what he thought my greatest limiting factor was in my climbing.

“I think it has a lot to do with one little question. Is 5.12 hard?” he asked. I knew the answer was supposed to be no.

“It is for me,” I said.

“That’s your limit. If you believed 5.12 was piss-easy, you’d be climbing harder. I believe you think certain grades are hard and that’s what limits you. Are there 5.9s and 5.10s that are hard? Yeah. Are modern-day 5.9s and 5.10s hard? No. There needs to be a shift in your mind to ‘I’m capable of doing this. I can do this.’ I see that shift in people sometimes, and that’s really powerful.”

I wish I could tell you that I worked Free Willy until I could do it blindfolded and then triumphantly sent it as my friends cheered below—but I didn’t. It might have been possible if I’d spent two months single-mindedly attacking that route, but my real goal wasn’t to climb Free Willy. It was to become a better climber. I can confidently say I reached that goal. A month after wrapping up the challenge I found myself in Sinks Canyon, Wyoming, with my friend Dakota and no guidebook. Dakota encouraged me to pick a route that looked fun and give it a go with no beta, something I’d never done before. As the hot Wyoming summer sun rose and threatened our ability to climb at all, it was my only option. I cruised up the lower section. The difficulty increased gradually—as did the length, when I climbed over a bulge and found six more bolts than I’d anticipated. But I fought on, figuring out tricky sequences, finding hidden footholds, and pulling on shallow pockets. When I clipped the chains I was pretty surprised that I’d made it. Later, I located the route in the guidebook: Action Candy (5.10a). While the climb wasn’t easy, not knowing the grade, I went at it with full confidence. Maybe Sjong was right. Then a week later I led another 10a. Then another. I hadn’t completed my absurd goal of jumping two number grades in two months. But I had gone from leading 5.9 to leading 5.10 confidently outside. It felt significant.

At the end of two months, the challenge didn’t end. It changed. It became a lifestyle. I wasn’t ready to stop pushing myself, and without skipping a beat I signed up for two more months of training with Sjong and Peters, this time through their online service as a paying customer. I destroyed the Ben & Jerry’s pint in my freezer (with my mouth), then resumed life. As an athlete.

The Four Types of Breathing

Sjong divides breathing into four modes. You can think of them like gears on a manual car; they exist on a spectrum. The higher the gear, the more your core is engaged, but the faster you’ll fatigue. Your breath is also a way of expressing intensity, which should match the difficulty.

- Gear 1: Deep, relaxing breath. As it sounds, a deep breath when you’re in a relaxed position on the wall will help you rest and reset your stress level.

- Gear 2: Tsaaat! The Sharma breath. You are forcing air out of your mouth through pursed lips. This is the gear you’ll be in for most moderate climbing. Breathing audibly will help remind you to keep breathing.

- Gear 3: AHHHH! The Ondra breath. More of a scream. You are restricting airflow with your diaphragm to keep your core tight on a difficult move, but still breathing.

- Gear 4: Holding your breath. In order to maximally engage your core muscles, you’ll need to hold your breath fully. This should be done only briefly and reserved only for the hardest moves. Resume breathing as soon as possible after.

How to Get Stronger

Different training loads will cause your muscles to adapt in different ways. Target these times for the desired adaptations.

- Max Strength. Increases muscle recruitment (allows you to contract more muscle fibers). Improves strength without increasing muscle size. To achieve: 4 to 10 seconds under tension. Weight: 85 to 100% of one-rep max

- Sarcomere Hypertrophy. Increases the density of your muscle, adding some size and strength, but also weight. Do this selectively. To achieve: 10 to 20 seconds under tension. Weight: 75 to 85% of one-rep max.

- Sarcoplasmic Hypertrophy. Increases the size of the muscle, but decreases muscle density. Good for bodybuilders, not climbers. To achieve: 20 to 45 seconds under tension. Weight: 60 to 75% of one-rep max, to failure

- Muscular Endurance. Beyond 45 seconds, you stop training muscle strength and begin solely training endurance. Keep in mind that training strength will also increase endurance and may be a more valuable use of your training time.

Understanding Macronutrients

Every calorie you consume can be broken down into a macronutrient category: carbohydrates, protein, fat. They all play an important role in your health and performance. The percentages listed here are what Rigby recommends a climber get as the ratios for their total daily calories. Alcohol is technically a macronutrient, unfortunately Rigby says, “Most people wouldn’t say that alcohol is an important part of daily nutrition.”

- Carbohydrates (4 calories per gram, 55-65% of diet). Carbohydrates are fuel that we can’t store a lot of. They’re much more efficient at producing large amounts of energy in a limited time than fats. Carbs find most of their glory in anaerobic training, but even for endurance athletes who are doing aerobic activities, carbohydrates are still important. If you burn carbohydrates aerobically, you will still produce about twice as much energy per molecule as you do from fat. Carbohydrates help you perform at a greater level of intensity than fats themselves allow.

- Fats (9 calories per gram, 15-30% of diet). Another fuel, but we have at least a small need for fat in our diet regardless of energy. We’re always burning fat. Our body at rest is burning fat. Fat is the most efficient energy system, and you have basically an unlimited supply of it. You can get more out of each fat molecule than anything else, just not in a short amount of time. Fat has a small structural role in creating hormones, and it’s part of our cell membranes, so we need dietary fat just to keep our bodies healthy.

- Protein (4 calories per gram, 15-25% of diet). Protein is not a fuel source, but we as athletes will still benefit from eating a lot of it. It’s primarily structural material, not just for your muscles, but for your entire body. Basically everything in your body is made out of protein to some extent. Even your bones are 30% protein. Our bodies are protein. We need to support it with dietary protein. Rigby believes that 20g every three hours, through food or protein powder, is the ideal amount to maximize absorption. There’s a significant amount of diminishing returns above 20g, and after 40g you’ll be excreting (pooping) all the extra. Eating extra protein will not curse you with a bulky bodybuilder bod. That takes years of hypertrophy-focused weightlifting. No one ends up Mr. Universe because they ate too much salmon.

Sample Training Week

Monday

- Rest day

Tuesday

- Warm up

Bouldering, 6-8 problems, 3 min. rest between each - Hangboarding

10 seconds on / 10 seconds off (x3), 4-10 sets, rest 4 min. between each - TRX Shoulder Strengthening

TRX reverse flys, TRX Y’s, and TRX I’s, 15 reps each per set, 3-6 sets, rest 1 min. between each - TRX Core Routine

1 min. each: TRX plank, TRX reverse crunches, TRX mountain climbers, TRX plank (again), TRX oblique crunches

Wednesday

- Warm up

Bouldering, 6-8 problems, 3 min. rest between each - Projecting

Project 2-6 boulder problems, rest 10 min. between each - Shoulder Fitness

Dumbbell shoulder presses, dumbbell lateral raises, dumbbell reverse fly’s, dumbbell front raises, 12 reps each per set, 3-6 sets, rest 1 min. between each - Shoulder Recovery Routine

Band external rotation, band elevated external rotation, band internal rotation, lying dumbbell external rotation, 20 reps each, 2 sets, no rest between

Thursday

- Rest Day

Friday

- Warm up

Bouldering - Back and Bicep Routine

Barbell bent-over rows, dumbbell bent-over rows, dumbbell bicep curls, dumbbell hammer curls, pull-ups, 12 reps each, 2-5 sets, rest 1 min. between each set - Shoulder Recovery Routine

Saturday

- Warm up

Route climbing, 4-6 routes, 8 min. rest between each - Hard/Easy/Hard

Climb a hard route, easy route, hard route in a row, 3-6 sets, 15 min. rest between each - TRX Side planks

Hold one minute on each side, 3-5 sets, 1 min. rest between each

Sunday

- Climb Outside

This day is up to you! Go outside and climb as many routes of whatever difficulty you want. Have fun! - Shoulder Recovery Routine

Climbing Supplements

Brian Rigby recommends the following for route climbers. All of them are known to be safe when taken at the recommended dosage.

- Creatine. The creatine phosphate system is the primary energy system used during climbing moves. No other substance in our body is capable of producing as much energy in as short a time as creatine. Supplementation can increase your creatine stores by about 33%.

- Beta-Alanine. Helps to buffer muscle fatigue, which means decreased pump and increased power-endurance after one to four minutes of work. Not very helpful for boulderers.

- Caffeine. Helps you focus and ignore pain and pump to some degree, which allows you to push a little bit harder.

- Citrulline Malate. The least-proven supplement here. Citrulline helps to dilate the blood vessels, increasing blood flow. Malate is a rate-limiting ingredient of the citric acid cycle, which is how we produce aerobic energy. These two ingredients may allow the body to pump more oxygen and process it more efficiently to increase power-endurance just a little bit. Tastes sour!

Meet the Team

Coach

Justen Sjong

Trainer

Kris Peters

Nutritionist

Brian Rigby

This story originally appeared in the February 2016 issue of our print edition and is reproduced here for free. Sign up with a Climbing membership, now just $2 a month for a limited time, and you get unlimited access to thousands of stories and articles by world-class authors on climbing.com plus a print subscription to Climbing and our annual coffee-table edition of Ascent. Please join the Climbing team today.

The post What Happens When a 5.9 Climber Starts Training Like a Pro? appeared first on Climbing.