Henson also discussed the importance of therapy as a tool for healing, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, and emphasized the value of destigmatizing mental health issues for African Americans — a task she undertook by starting the Boris Lawrence Henson Foundation, named for her father, who struggled with challenges resulting from his military service in Vietnam. The foundation works to change perceptions in the African American community and make it easier for individuals to seek treatment.

In the world of entrepreneurship, Henson spoke about creating TPH by Taraji, a scalp and haircare line. Like with her advocacy and work in Hollywood, she was driven to create something that would serve her and other people like her. She looked for a product to help take care of her hair no matter what style she wore, but “nothing existed. So just like Black women — Black people — have done since the beginning of time, when it doesn’t exist, what do we do? We create. So that’s what I did,” she said.

Though the celebrations looked very different than in years past, Henson’s passion for her craft and commitment to advocacy were infectious.

“I’m glad I was on mute, because I’m over here screaming ‘Yes!’ in my living room to everything that you have to say,” Corbin-Contreras told Henson.

Rakesh Khurana, Danoff Dean of Harvard College, presented Henson with the Artist of the Year plaque, which she held up in her own screen. Not being able to gather in person, Henson lamented, was the only downside of the occasion.

The Thursday event capped off three days of programming, including a student-organized, peer-to-peer dialogue inspired by Henson’s work and legacy called “And Scene: Breaking the Cycle of Performative Resilience” and “Mindful of Race: Embodied Practice & Dialogue,” a wellness workshop with yoga teacher Abraham Dejene for students of color, hosted in partnership with the Center for Wellness and Health Promotion.

Since its establishment in 1981 by the President and Deans of Harvard University, the Harvard Foundation for Intercultural and Race Relations has pursued its mandate to “improve relations among racial and ethnic groups within the University and to enhance the quality of our common life,” through programming, activities, and events like Cultural Rhythms, which began in 1986.

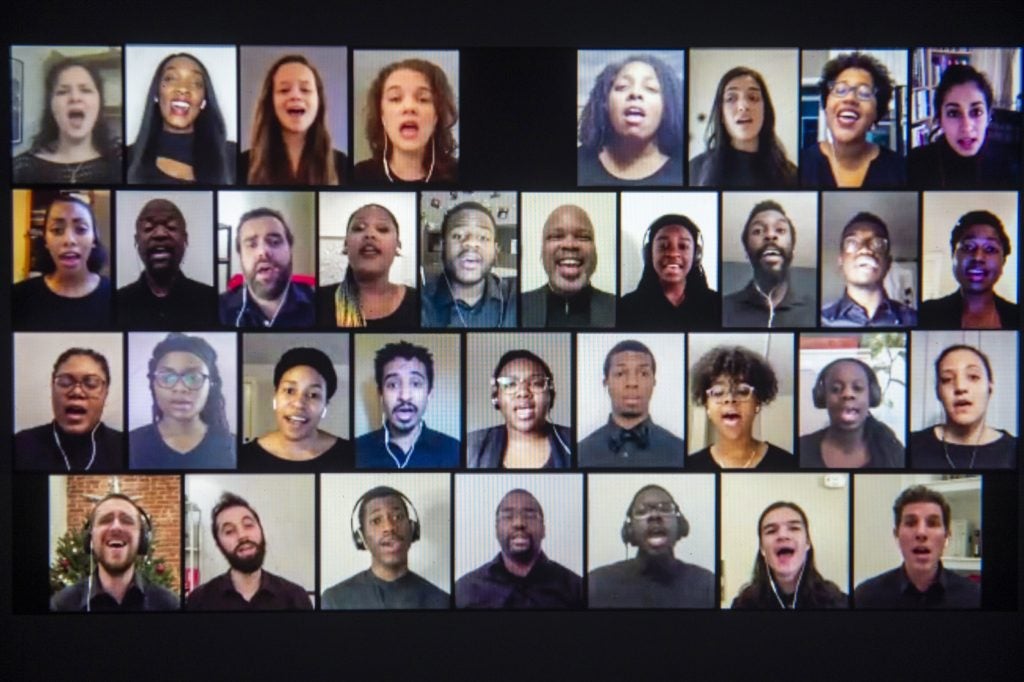

As in previous years, students participated in all parts of the program. The Kuumba Singers of Harvard College performed a medley of songs, and Remka Nwana ’23 performed an original spoken-word piece. Closing remarks were given by Harvard Foundation intern and College junior Aaron Abai, and the entire evening was hosted by Derrick Ochiaga ’22 and Mariana Haro ’23.

“Cultural Rhythms has consistently uplifted students, student organizations, and cultural experiences that have historically been marginalized at Harvard, and placed them at the center of our community,” said Sheehan Scarborough ’07, M.Div. ’14, Harvard Foundation senior director, in his remarks. In the midst of upheaval brought on by COVID-19 and the ongoing threats of racism and xenophobia, “it has encouraged students to stake a claim to declare: I belong here. I too, am Harvard.”